If you’ve ever been so angry you saw red, stand back, because the phrase “blood in your eye” gets taken to a whole new level by the horned lizard. They defend themselves from certain predators by shooting jets of blood from their eyes.

They do WHAT now?

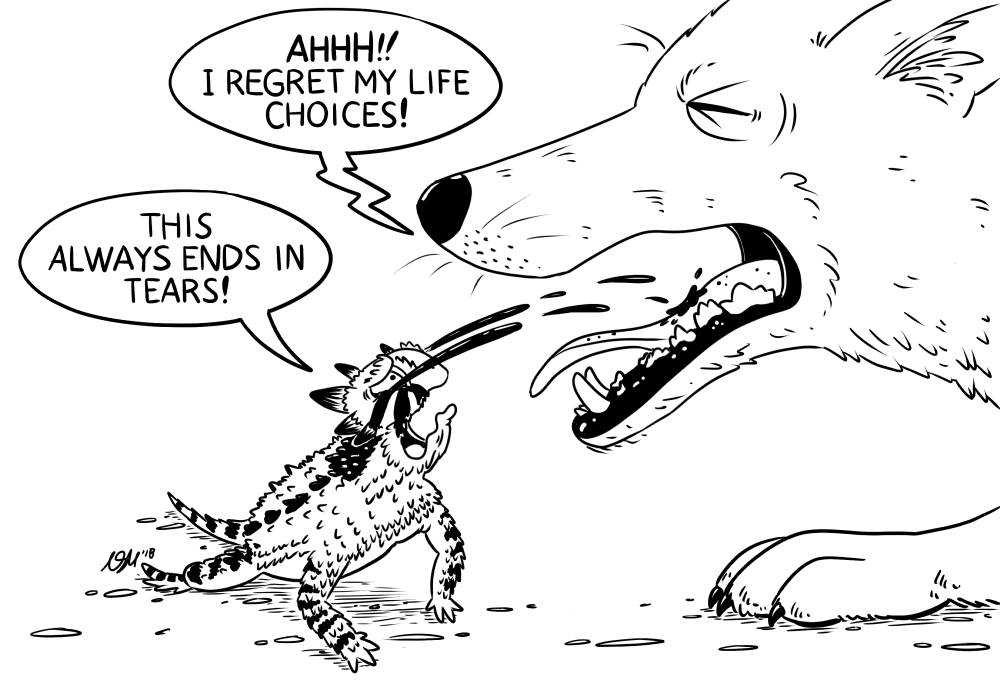

Well, they do…this:

To be fair, they don’t pull that trick out right away, or for just anyone.

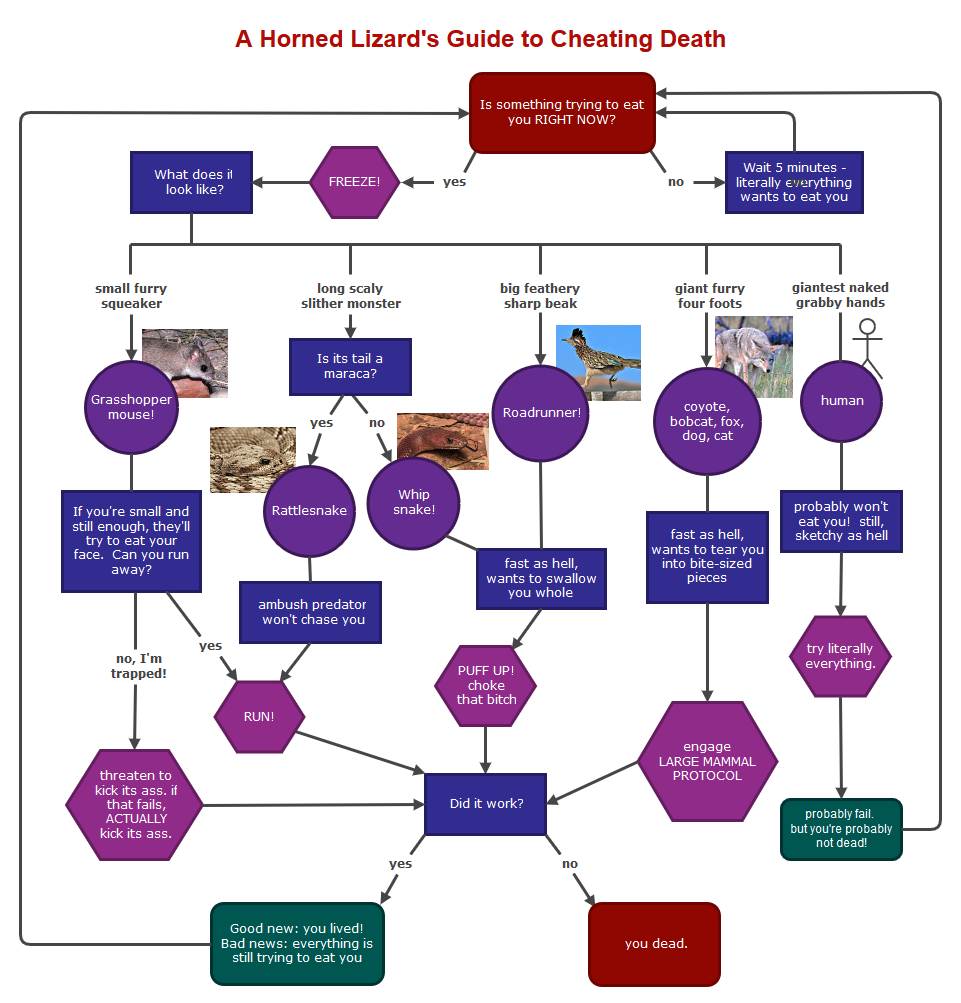

Horned lizards mostly rely on camouflage and a freeze response to keep from being noticed by the many, many things that are trying to eat them. If they do get spotted, they have an impressive toolbox of defense mechanisms and a knack for identifying the right tool for the job.

Large mammals, like coyotes, kit foxes, and bobcats, present a different set of problems from the rest. The horned lizard can’t hope to outrun them, isn’t big enough to intimidate them, and will probably be torn to pieces before being eaten, not swallowed whole.

With this type of predator, they have to pull out an entirely new set of tricks.

First they try an airborne method of escape: they lift their tail in the air to entice the predator to attack there, instead of the head. Large mammals that take the bait often lift the lizard and toss it; the horned lizard then freezes where it lands to make the most of its camouflage. A lot of the time, the predator simply can’t find it again. (There’s a moral to be had here about playing with your food…).

If that fails, here’s where things get dicey for the horned lizard: its next best defense involves its head going inside the predator’s mouth. If the predator crushes their skull or rips their head off, it’s game over, but the horns on their heads usually keep a predator from biting down too hard. That buys the horned lizard enough time to squirt the ol’ eye blood directly into the carnivore’s mouth.

Although it only tastes a little acrid to us (yes, the researchers licked it – all in the name of science, you understand), canine and feline predators have an extremely negative response to the taste. They gape their jaws, opening and closing their mouths repeatedly (which is super convenient for escaping prey), start drooling heavily, and wipe their muzzles in the grass; for the next 15 minutes, they’re focused on little else but getting this stuff out of their mouths.

Like a college student on their first tequila hangover, it probably swears off horned lizard snacks for life. And the horned lizard gets away.

Ok, but how do they DO that?

The ability to squirt blood from the eyes turns out to be an aftermarket hack onto a feature that comes standard in reptiles.

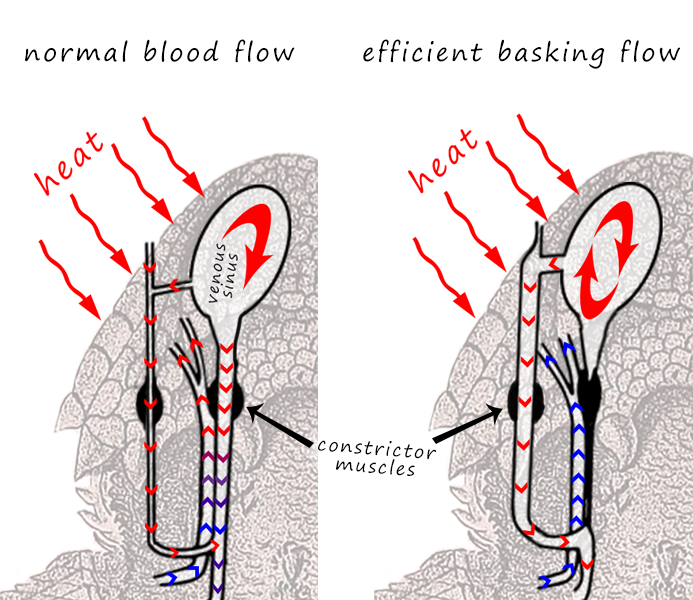

If you’re a cold-blooded animal, warming yourself up after sunrise is step one to getting on with your day. It turns out reptiles don’t heat up evenly, though – the head warms much faster than the body, and the normal flow of blood keeps the heat from being redistributed. The main highways for bringing blood in and out of the head run alongside one another, for the same reason we build our roads that way – if you’re going to carve out a path, you might as well use it to travel both directions. This isn’t a problem if you’re one temperature all over like us, but for a basking lizard, it means the warmer blood flowing out of the head is pressed right up against to the cooler blood flowing into the head.

It’s like packing a hot meal right next to the ice cream – by the time you get where you’re going, everything is going to be lukewarm.

The best way to fix this is to force a detour. Reptiles developed rings of muscle around the main veins exiting the head in order to pinch off the blood flow and force it down a side street where heat-thieving arteries aren’t an issue.

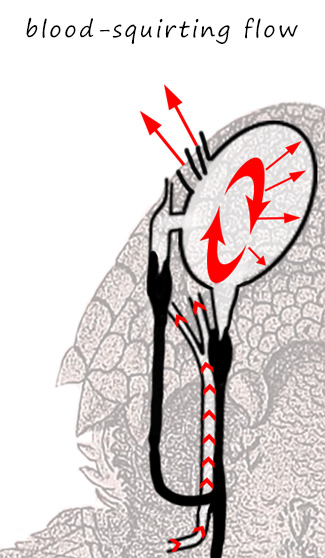

This is the manufacturer default for reptiles, you could say. But it turns out the ability to create high blood pressure in your head has useful applications, so some reptiles tricked out this feature further with muscles that pinch off the detour as well, sealing off all exits.

Horned lizards took this system one step further – instead of building up a little pressure in the eye, they build up enough pressure to burst through the wall of their sinuses and force blood through their tear ducts to be propelled up to 6 feet away.

So this is what happens when a horned lizard gets harassed: the rings of muscle around their veins shut off blood flow out of the head, pressure builds until blood pools in their sinuses, and their eyes get visibly puffy. They’re locked and loaded.

It has to be the right kind of harassment though, from a coyote, bobcat or your friendly neighborhood dog. In fact, they won’t even fall for a human pretending to be a dog (yes, the same research team that licked the blood got on all fours to paw and bark at them…science is serious business, y’all). Their response is so specific that attempts to study blood squirting were foiled for decades, until researchers trained a dog to paw at and gently nibble the creatures.

Once the horned lizard is primed to shoot blood, one last trigger is needed – the lizard usually won’t eject the blood unless the touch receptors on their head are stimulated. In other words, the horned lizard has to think its head is in the predator’s mouth before it looses its best weapon.

There’s a very good reason for this – that violently distracting response canines and felines have to horned lizard blood only happens when the blood hits the tissues of their mouth. If the lizards squirt too soon, the blood might land on the ground, or their fur, and have no effect. Even with better aim, hitting the eyes is completely ineffective; squirting blood up their nose has a delayed response, probably due to the time it takes for the blood to drain through their sinuses into their mouth.

If a horned lizard wants to be very sure it’s not wasting precious blood, they have to be in the predator’s mouth before they fire.

How did that even become a thing?

Chances are, it began as a (happy) freak accident. Researchers suspect that the compound in their blood that causes the ‘icky icky ew’ face in canines and felines is a result of their diet.

Horned lizards, as it turns out, specialize in eating harvester ants…a species of insect that few others dare to eat due to their potent venom. We know that horned lizards detoxify the ant venom enough that it won’t kill them, but the idea – not yet proven – is that a compound related to that process (either the detoxified venom, or something used to detoxify it) happens to taste really bad to some species.

Reptiles outside of the horned lizard’s genus do occasionally leak blood from their eyes in moments of acute stress. Being eaten is surely stressful, so it seems likely that the first instances of this defense were inadvertent, just a quirk of high blood pressure. One day, a horned lizard got attacked by a coyote, stressed out over its shuffle from the mortal coil, bled from the eyeballs, and – miraculously – was spat out! The compound already in the lizard’s blood was just the right shape to match a chemical receptor in the coyote’s mouth.

But in order to save the lizard’s life, the blood had to make direct contact with the predator’s mouth. Sure, blood would also be spilled after the predator started chewing, but who can survive that? And at that point, the blood is diluted by everything else the predator is tasting…more effective to give the them a concentrated taste of blood before serious injury could occur.

Lizards that bled from the eye had a higher survival rate, and the ones that bled more had a higher survival rate still. That’s a slippery slope to projectile eye blood, my friends.

Since it was really only worth the blood loss when used on predators that would be repelled, their responses became honed to specific cues.

It’s not the most conventional solution to self-defense, but hey, it works for them – and they get extra points for turning a predator’s taste for blood against them.

Learn More

References

Heath, J. (1966). Venous Shunts in the Cephalic Sinuses of Horned Lizards. Physiological Zoology, 39(1), 30-35. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30152764

Middendorf, G., & Sherbrooke, W. (1992). Canid Elicitation of Blood-Squirting in a Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum). Copeia, 1992(2), 519-527. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1446212

Middendorf, G., & Sherbrooke, W. (2004). Responses of Kit Foxes (Vulpes macrotis) to Antipredator Blood-Squirting and Blood of Texas Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma cornutum). Copeia, 2004(3), 652- 658. Available at: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1643/CH-03-157R1

Sherbrooke, W. (2000). Sceloporus jarrovi (Yarrow’s Spiny Lizard). Ocular sinus bleeding. Herpetological Review 31(4), 243. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305612339

Sherbrooke, W. (2008). Antipredator Responses by Texas Horned Lizards to TwoSnake Taxa with Different Foraging and Subjugation Strategies. Journal of Herpetology, [online] 42(1), 145-152. Available at: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/07-072R1.1

Sherbrooke, W. (2012). Negative oral responses of a non-canid mammalian predator (Bobcat, Lynx rufus; Felidae) to ocular-sinus blood-squirting of Texas and regal horned lizards, Phrynosoma cornutum and Phrynosoma solare. Herpetological Review, [online] 43(3): 386-391. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286024808

Sherbrooke, W., & Mason, J. (2005). Sensory Modality Used By Coyotes In Responding To Antipredator Compounds In The Blood Of Texas Horned Lizards. The Southwestern Naturalist, 50(2):216–222. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/511

Image Source

The blood flow schematics in this article were created by me, using a sketch of P. orbiculare provided by Biodiversity Heritage Library under a CC BY 2.0 license. Heath (1966) Fig 5 served as the template for the schematics of the major vessels.

The horned lizard defense flow chart uses the following images of their predators:

Chihuahuan grasshopper mouse by American Society of Mammalogists (CC BY 2.0)

Rattlesnake by Ann W (CC BY 2.0)

Sonoran Coachwhip snake by Andrew DuBois (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Roadrunner by Teddy Llovet (CC BY 2.0)

Coyote by Larry Lamsa (CC BY 2.0)

The resulting derivative works are available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, should anyone find them useful.